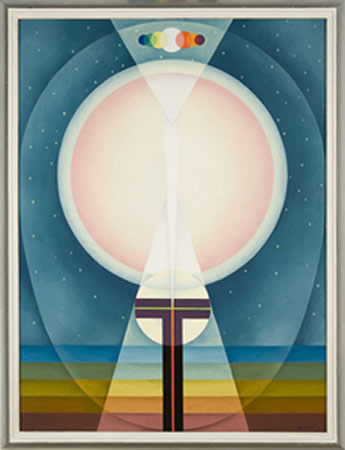

Emil Bisttram’s artistic career is of special interest because of the fascinating array of spiritual, philosophical, and scientific traditions he brought to bear on his painting. Profoundly spiritual and convinced that all intellectual disciplines lead to divine truth, Bisttram enriched his compositions with references to such varied subjects as electricity, rebirth, the growth of plants, the healing power of the dance, planetary forces, the fourth dimension, and the male and female principles of nature.

Bisttram’s essential goal in building his compositions, however, was personal redemption. For Bisttram, dividing space on a blank sheet of paper replicated such proportional divisions as were made by the Creator when He separated day from night, and earth from water. Bisttram’s essential belief was that harmony was proportional, and that making harmonious, proportional divisions on a sheet of paper was a productive, life-giving, redemptive enterprise that combated negativity and disharmony.

The manner that Bisttram used to proportionally divide his compositions was dynamic symmetry, a method of picture composition based on Euclidean geometry developed by Jay Hambidge (1867-1924). Bisttram used dynamic symmetry for the structure of his representational, abstract (cubist and futurist), and transcendental (non-objective) compositions. For Bisttram, dynamic symmetry functioned as a compass that guided him through the many stylistic experiments he undertook, and provides the essential coherency for his work as a whole.

Bisttram was using dynamic symmetry by 1920, when he was just beginning to establish himself as an artist. At the same time he also became interested in various spiritual systems generally associated with the occult, including theosophy, Swedenborgianism, and Rosicrucianism. By correlating these spiritual systems with dynamic symmetry, he felt that he was pictorially reconciling religion and science, which was perhaps the most important factor motivating his work. This was a conscious aim on his part and one which he expressed frequently:

Through self-discipline and contemplation, tolerance and vision he [the artist] will become the synthesizer of the reality of religion and the truth of science. (Emil Bisttram, “Art’s Revolt in the Desert,” Contemporary Arts of the South and Southwest 1, no. 2: Jan.-Feb. 1933, 11.)

Bisttram began by applying dynamic symmetry to representational compositions; after his move to Taos, New Mexico, in 1931, he began working with cubist and futurist styles, arriving at an aesthetic of pure geometric form by 1938, when he and nine others founded the Transcendental Painting Group. Tracing Bisttram’s transition from representation to abstraction through his mystical and scientific use of dynamic symmetry, provides a fruitful approach to appreciating his intentions.

The key theoretical construct with which Bisttram worked was the theory of opposites that functioned within H. P. Blavatsky’s theory of the ether, which is examined in the context of specific works of art. This principle of opposites also functioned within Swedenborgian theology, which Bisttram read in the 1920s, and in Jungian psychology, which he read in the 1930s. The link between these theories is that they all present similar methods for redemption. Bisttram’s goal of expressing these theories of opposing interrelated forces pictorially led directly to a constructivist handling of geometric forms.

During his lifetime, Bisttram was well-known across the Southwest and West. He had an impressive number of solo exhibitions at museums and university galleries, frequently won awards in group exhibitions, and was regularly invited to serve on juries. In 1931 he was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship to study in Mexico with Diego Rivera.

Bisttram was also active in the Taos art scene: in 1933 he was a founding member of Taos Heptagon, regarded as the first art gallery in Taos, and in 1939 organized La Fonda Gallery in the La Fonda de Taos Hotel. He participated in government mural programs, and served as supervisor for Northern New Mexico for the Treasury Relief Art Project (TRAP). He was a founding member of two associations of artists in Taos (1934, 1952), and served as president of the Taos Artists Association for two terms (1939, 1940).

Through his membership in the Transcendental Painting Group, his work came to the attention of Hilla Rebay, who included him in a number of group exhibitions at the Museum of Non-Objective Art, now the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum (1940, 1944, 1950).

Beginning in 1932, he ran an art school during the summers in Taos, and took private students during the winters. In 1941 he began teaching in Phoenix during the winters. He established a presence on the West Coast while operating his art school in Los Angeles (1945-1951). In 1961, he was included in the only exhibition ever devoted to dynamic symmetry, which was organized by the Rhode Island School of Design. In 1973, he was appointed to serve on the New Mexico Arts Commission, and on his eightieth birthday, the governor of New Mexico proclaimed “Emil Bisttram Day.”

Since Bisttram’s death, his work has been exhibited primarily in the context of large group exhibitions. The spiritual dimension of Bisttram’s painting and the importance of the Transcendental Painting Group were recognized by the inclusion of paintings by Bisttram and three other members – Lawren Harris, Raymond Jonson, and Agnes Pelton – in Maurice Tuchman’s The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890-1985 (1986). Spiritual painting has also been practiced by representational painters, which is shown in Cosmic Art (1975), Raymond Piper’s survey of 20th c. spiritual painting, in which Bisttram was also included.

Bisttram’s transcendental paintings, which were produced after 1936, are usually classed with the “second wave” of American abstractionists – those artists who came to maturity during the 1930s under the influence of Picasso and Kandinsky. This categorization of Bisttram is generally correct, and points to the essential interest of his work – the manner in which he made the transition from representational to abstract painting, and the relationship of his work to Kandinsky’s.

The “second wave” abstractionists have been examined in large exhibitions that in many cases include both the Transcendental Painting Group and the American Abstract Artists. The association between these two groups has been made primarily by collectors interested in 1930s abstraction. Theme & Improvisation: Kandinsky & the American Avant-Garde 1912-1950 (1992), a broad overview of these trends, provides the most comprehensive treatment of Bisttram and the Transcendental Painting Group.

Since Bisttram also worked in a representational mode using subjects related to New Mexico, he has been included in books and exhibitions devoted to the first generation of New Mexico painters. Jackson Rushing’s inclusion of a number of Bisttram’s abstract works in Native American Art and the New York Avant-Garde (1995) recognized his contribution to the development of modernist forms in American art.

Since Bisttram’s death only one solo exhibition of his works has been mounted at a museum, an exhibition of his works on paper from the Anschutz Collection at the Harwood Museum in Taos in 1983. A monograph on Bisttram was published by the dealer Walt Wiggins in 1988.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Blankenship, Tiska and Ed Garman. Vision and Spirit: The Transcendental Painting Group. Albuquerque: Jonson Gallery, 1997.

Coke, Van Deren. Taos and Santa Fe: The Artist’s Environment. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1963.

Eldredge, Charles C., Julie Schimmel, William H. Truettner. Art in New Mexico, 1900-1945: Paths to Taos and Santa Fe. Washington, DC: National Museum of American Art, 1986.

Hay, Robert C. “Dane Rudhyar and the Transcendental Painting Group of New Mexico, 1938-1941.” MA diss., Michigan State University, 1981.

Knott, Robert. American Abstract Art of the 1930s and 1940s: The J. Donald Nichols Collection. Winston-Salem: Wake Forest University, 1998.

Levin, Gail and Marianne Lorenz. Theme & Improvisation: Kandinsky & the American Avant-Garde 1912-1950. Dayton: Dayton Art Institute, 1992.

Luhan, Mabel Dodge. Taos and Its Artists. New York: Duel, Sloan, & Pearce, 1947.

Mecklenburg, Virginia M. The Phillip Frost Collection: American Abstraction 1930-1945. Washington, DC: The Smithsonian Institution Press, 1989.

Monte, James and Anne Glusker. The Transcendental Painting Group, New Mexico 1938-1941. Albuquerque: Albuquerque Museum, 1982.

Nelson, Mary Carroll. The Legendary Artists of Taos. New York: Watson-Guptill Publications, 1980.

Piper, Raymond and Lila K. Piper. Cosmic Art, ed. Ingo Swann. New York: Hawthorn Books, Inc., 1975.

Porter, Dean A., Teresa Hayes Ebie, Suzan Campbell. Taos Artists and Their Patrons, 1898-1950. Notre Dame: The Snite Museum of Art, 1999.

Reeve, Kay Aiken. “The Making of An American Place: The Development of Santa Fe and Taos, New Mexico, as an American Cultural Center, 1898-1942. Ph.D. diss., Texas A & M University, 1977.

Rushing, W. Jackson. Native American Art and the New York Avant-Garde: A History of Cultural Primitivism. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1995.

Strickler, Susan E. and Elaine D. Gustafson. The Second Wave: American Abstraction of the 1930s and 1940s: Selections from the Penny and Elton Yasuna Collection. Worcester: Worcester Art Museum, 1991.

Trenton, Pat. Picturesque Images from Taos and Santa Fe. Denver: Denver Art Museum, 1974.

Tuchman, Maurice. The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890-1995. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1986.

Udall, Sharyn. Modernist Painting in New Mexico 1913-1935. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1984.

Wiggins, Walt. The Transcendental Art of Emil Bisttram. Ruidoso Downs, NM: Pintores Press, 1988.

Witt, David. Emil James Bisttram. Taos: The Harwood Foundation, 1983.